Interest rates have been low in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), raising concerns about financial stability. In particular, the profitability and strength of financial firms may suffer in an environment of prolonged low interest rates. Additional vulnerabilities may arise if financial firms respond to “low-for-long” interest rates by increasing risk-taking. In light of these concerns, BIS, the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS), mandated a Working Group to identify and provide evidence for the channels through which a “low-for-long” scenario might affect financial stability, focusing on the impact of low rates on banks and on insurance companies and private pension funds.

Nevertheless, banks generally appear to have found ways to shield their overall return-on-assets (RoA) from prolonged low interest rates (including by cost-cutting, strengthening fee-based income, extending asset duration and increasing exposure to the housing sector), although some of these adaptations may prove less viable going forward (e.g. cost-cutting). Accordingly, econometric simulations of the effect of a low-for-long scenario for interest rates over the next decade or so suggest that, compared with a “baseline” scenario in which interest rates rose gradually and in line with most observers’ expectations, banks would generally experience reduced net interest margins but much less damage to overall profitability.

1.1 Baseline scenario

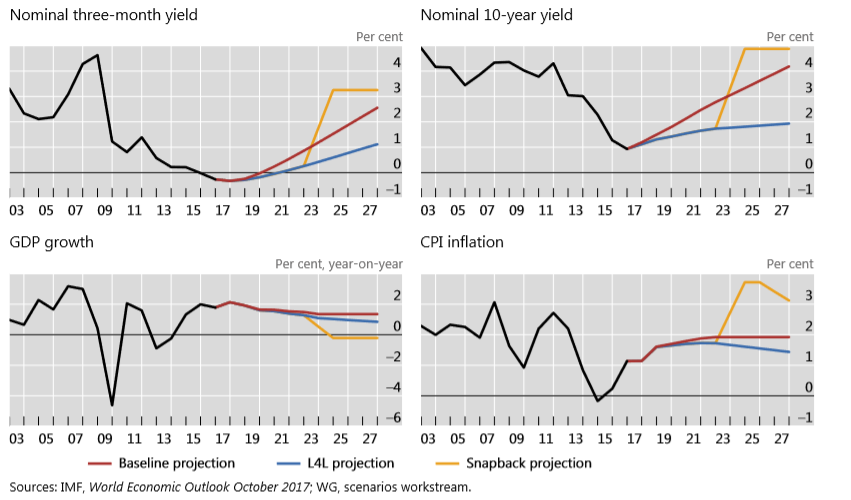

The baseline scenario (see Graph, red lines) uses IMF projections, which are assumed to represent mainstream projections. IMF projections from the October 2017 World Economic Outlook (WEO) are used and run through 2022 (IMF (2017)). The WG’s extension of the IMF projections beyond 2022 starts with pinning down the value of the short real rate and inflation at the terminal date (2027). The economy is assumed to have reached a steady state with output at potential

1.2 Low-for-long scenario

Relative to baseline, the low-for-long scenario (see Graph, blue lines) projects a lower path for interest rates, actual and potential GDP growth and inflation. In particular, inflation undershoots the policy target. The inflation rate and the nominal short rate all start at the same level as in baseline in 2017, but end up respectively 100, 50 and 150 basis points lower than baseline by 2027. The 10-year yield is set so that the term spread converges linearly to a terminal value which is half the average term spread between 1999 and 2016. This is motivated by the possibility that low interest rate environments reduce term premiums.

1.3 Snapback scenario

The snapback scenario (see Graph, yellow lines) features a rapid run-up in inflation, starting partway through the projection period (in 2023), that engenders a correspondingly rapid increase in short- and long-term interest rates. The surge in inflation could be motivated by any number of factors; here, it is assumed that a slower rate of potential GDP growth implies a wider output gap and a heightening of price pressures. Inflation rises 2 percentage points above. The 10-year yield rises even more, in part reflecting the re-emergence of an inflation risk premium in the term spread. These higher rates induce a recession, but because inflation remains above target, interest rates remain elevated.

Euro Area

2.1 How do low rates impact banks?

Low rates may diminish the resilience of banks by restricting profitability, and thus the ability to replenish capital after a negative shock, and by encouraging risk-taking, thus increasing the risk of future losses. The risks to financial stability from a low interest rate environment depend on the extent to which profitability is reduced and the degree to which measures taken to offset such losses increase vulnerability.

Low rates affect bank profitability mainly through net interest margins (NIMs). Specifically, when short-term interest rates decline, banks may be unwilling or unable to lower deposit rates below a given level, even as returns on loans and other assets decline, and this should lower NIMs. In particular, if market rates become negative, banks may be unable to adjust deposit rates accordingly. A flatter yield curve should also lower NIMs, to the extent that banks’ loans and other assets have longer durations than their liabilities. Banks can offset lower NIMs by issuing riskier loans and through business adjustments, for instance by increasing fee-based business. And, in an environment of deficient aggregate demand, low interest rates may support loan demand, thus potentially moderating reductions in NIMs and return-on-assets (RoA). Nevertheless, these offsets may prove difficult and provide only one-off or temporary

Low interest rates may also trigger a search for yield by banks, partly in response to declining profits, exacerbating financial vulnerabilities. Evidence from prior analyses suggests that banks may increase risk-taking in response to low rates through shifts toward lower quality lending in return for higher yields.

2.2 Banking Profitability

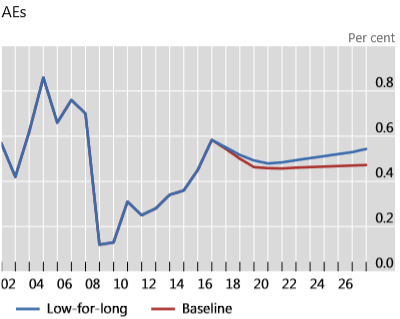

Overall profitability as represented by RoA is much less sensitive to interest rates and the undershooting of NIM.

Advanced Economies ROA under Different Scenarios

The bank’s business model can affect the sensitivity of its profits to interest rates. To the extent that the effect of interest rates on profitability works through lending and deposit margins, banks with extensive conventional lending and deposit taking activities would likely experience the largest effects of interest rates on their margins and profitability. Profits of banks that have a more diversified activities portfolio, and hence rely more on fee income, might be subject to a smaller impact from a decline in interest rates.

Interest-rate scenarios have been featured in a number of recent supervisory stress exercises in the United Kingdom, Germany, the euro area, Switzerland and the United States. These stress test results provide further evidence that lower interest rates can weigh on bank profitability. For example, the ECB exercise for interest rate risk in the banking book found that if interest rates remained at their low end-2016 levels, the net interest income of 111 significant euro area banks would fall on average by 7.5%.

Similarly, a BaFin/Bundesbank survey indicates that a move to higher rates would provide significant support to the profitability of smaller German credit institutions. Some stress tests incorporate adjustments in banks’ balance sheets or broader business strategies, which can potentially offset part of the earnings impact of low rates. In the exploratory scenario of the 2017 Bank of England stress test, UK banks indicated they would respond to a lower-for-longer rates scenario by cutting operating costs – particularly by closing branches and reducing employees – and increasing non-interest income (such as fees).

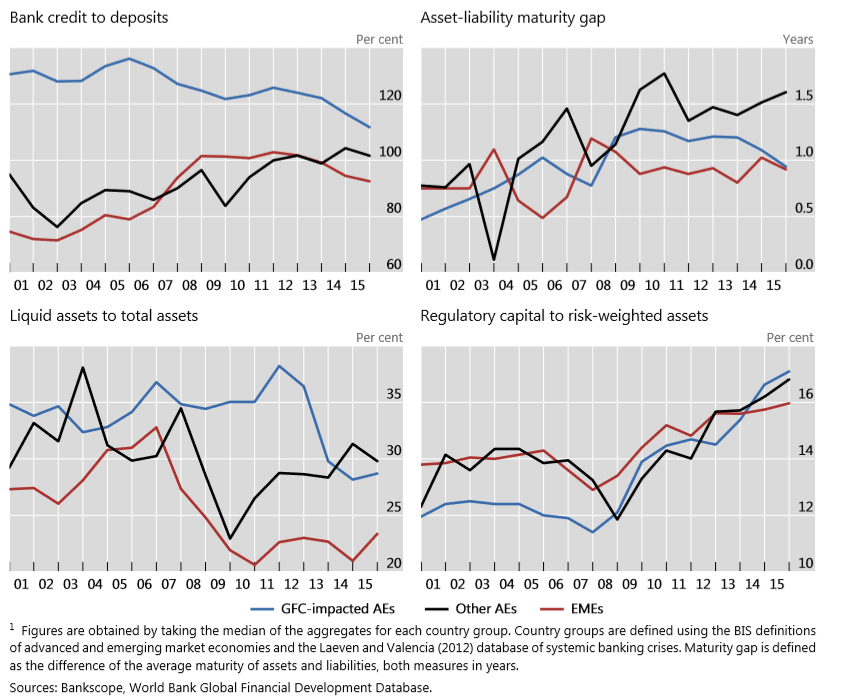

Changing Risk Characteristics for Advanced and Emerging Economies

The 2017 BaFin/Bundesbank exercise found that many small- and medium-sized German banks would consider mergers as a means to achieve cost efficiencies and business scale. However, banks’ strategic responses can also entail increased risks. One third of banks in the 2017 BaFin/Bundesbank exercise projected a deterioration in their CET1 ratios in part due to engaging in riskier lending activities. Stress tests can also gauge the vulnerability of banks to sharp snapbacks in interest rates. The 2016 analysis by the Swiss National Bank found that the impact of rates can depend on the magnitude of the shock. While a 200-basis point increase in rates would boost banks’ net interest margins, a 400-basis point increase would be expected to disproportionately boost the rates paid on bank liabilities and thus compress margins, on balance.

Sizeable interest-rate snapbacks – occurring alongside moderate recessions – featured in the US Federal Reserve’s 2013, 2014 and 2015 Dodd Frank Act Stress tests’ adverse scenarios. This analysis found that (for most banks) snapbacks that involved the yield curve shifting up and flattening and generating lower returns from maturity transformation implied relatively more stress relative to snapbacks that involve the yield curve shifting up and steepening. Both scenarios implied large unrealised capital losses to available for sale securities portfolios.

2.3 Impact of a snapback after prolonged low rates

A period of prolonged and historically low interest rates poses the risk that these rates may revert sharply and unexpectedly to higher levels, especially if the factors causing the initial low-for-long scenario are not well understood. The snapback scenario would represent a substantial shock: short-term rates rise by 300 basis points and longer-term interest rates rise even more, leading to a recession. Even if banks had not adjusted their portfolios and business models to low interest rates in the years before the snapback, they would be challenged by valuation losses on their longer-term securities, higher funding costs, increased delinquencies on their loans and reduced credit growth. As emphasised by the analysis of Swiss banks, in the event of a sharp snapback, these losses could exceed the benefits to banks of higher net interest margins. Although the WG found little evidence of a generalised rise in risk-taking in the low-interest-rate years following the GFC.

Banks have taken measures to offset reductions in net interest margins that could raise their exposure to interest rate snapbacks, including lengthening the maturity of their assets and raising their exposure to real estate loans. Our review of stress tests, the simulation exercise on Swiss banks, and the US experience with rising rates since the GFC suggest that banks may be putting themselves at more risk should interest rates rise abruptly, especially smaller banks that do not hedge their interest rate positions. Moreover, should interest rates remain low for a prolonged further period, and especially should supervisory and regulatory constraints loosen, more overt forms of risk-taking may become more prevalent.

3.1 Summary and financial stability implications

The evidence suggests that low interest rates depress net interest margins, especially where banking markets are very concentrated and if the level of short term rates is already relatively close to zero.

At the same time, econometric evidence and the experience of recent years suggest that, on average, banks have found ways to shield overall return-on-assets from prolonged low interest rates. In consequence, while a low-for-long scenario would likely depress NIMs to a material extent, RoAs for much of the banking system seem likely to be less affected.

However, the profitability of some banks or even some banking systems could suffer more considerably in a low-for-long scenario, depending on their business models, balance sheets and competitive environments. The WG found only limited evidence to support the view that prolonged low interest rates would induce a substantial degree of additional risk-taking. Aggregate measures of bank soundness generally have not deteriorated to a marked extent, including in the euro area.

That said, it is difficult to identify comprehensive and reliable measures of risk taking behaviour. Moreover, it is possible that the subdued extent of risk-taking in recent years may reflect greater supervisory and regulatory restraint in the wake of the GFC. There is also some evidence of banks stretching the duration of their assets and increasing their exposures to housing markets, both of which would increase their vulnerability to a sharp increase in interest rates. Even in the absence of a prior increase in bank risk-taking, a sharp snapback in interest rates would likely entail valuation losses on longer-term securities holdings, increased delinquencies on loans, and reduced credit growth, potentially overwhelming any profitability benefit from higher net interest margins.

If banks did adjust to low interest rates through riskier loans, greater duration mismatches and greater investments in interest-sensitive sectors such as housing, the adverse consequences of a snapback would be worse. The rises in yields that occurred in recent years were well handled by US banks. However, as illustrated by the case study of Swiss banks, sharper rate increases associated with major asset price corrections would likely have more dire consequences. If deposit rates were to rise faster than they have done in past cycles, their increase might outpace that of yields on assets, thus depressing – rather than boosting – NIMs.

SOURCE: CGFS Papers 61, BIS